Skillful teachers can shape even the most complex content into engaging stories that plant seeds of wonder—stories that invite students to investigate the world beyond the classroom door.

Mary Beth Wertime tells that kind of story. Mary Beth worked in international development and most recently as a Montessori teacher in a public school in the U.S. We met Mary Beth at the 2014 Human Systems Dynamics Conference and discovered our shared passion for generative teaching and learning in public schools—and our shared frustration with the current high stakes testing regime.

In this post, Mary Beth explains how five stories (called “Great Lessons” in Montessori schools) are told to children at the beginning of each year. She explains how these stories engage children in interdisciplinary explorations. She also addresses the structural difficulties of this inquiry-based approach in public schools where local, state, and federal testing requirements require frequent interruptions throughout the year.

The following post is based on the transcript from the January 4 HSD in Education Webinar led by Mary Beth Wertime.

What Are the Montessori “Great Lessons”?

Maria Montessori was one of the first female physicians in Italy. She opened a school in 1907 in Rome. She developed her methodologies and philosophies through careful observation of children. Montessori used her medical training, observation of the developmental stages of growth in children, and her association with scientists to study how students build concentration and self-discipline and learn to explore and discover.

Although many Montessori schools are private, there are 443 public Montessori schools in the United States as of 2014 (taken from Census Project of the National Center for Montessori in the Public Sector, 2014). Of these, many are primary schools (Ages 3 – 6), but over 100 schools serve adolescents. These schools serve 112,486 students in the U.S. There are not as many middle and high schools because Montessori did not develop methodologies for older students, but she did write about adolescents, and some educators developed materials for middle and high schools.

The groundwork for the “Great Lessons” can be found in two books by Maria Montessori: To Educate the Human Potential and From Childhood to Adolescence. However, it was her son, Mario Montessori, who took these ideas and wrote the Great Lessons or “the cosmic fables” or “the “cosmic curriculum.” You can find summaries of these Great Lessons in Montessori Today by Paula Polk Lillard and in Children of the Universe: Cosmic Education in the Montessori Elementary Classroom by Michael and D’Neal Duffy.

The idea of telling stories to highlight interdisciplinary study is not a new idea. It was written about in the 1800s. Mario Montessori, however, pulled together information and designed these stories to be part of how Montessorians teach in elementary school.

The cosmic stories, or the “Great Lessons,” are stories used at the beginning of each year to introduce the big ideas that the children will continue to investigate throughout the school year. It’s important to remember that these are impressionistic stories, and not every detail is given while telling each story. Their purpose is to whet the appetite and draw children into thinking about the world around them. The stories start from age 6 and are taught throughout the elementary curriculum. They are:

Notice that this is a nested sequence, beginning with the most expansive–the universe. Montessori thought that, rather than starting with the child’s town, then teaching about the state, and then each country, Montessori teachers should start with the universe because children are asking huge questions about life.

“Let us give them (the elementary children) a vision of the whole universe….all things are part of the universe and are connected with each other…This idea helps the mind of the child to become fixed.”(Montessori, p. 8)

If you look at the bottom of the stack of nested bowls in the picture, you can see that Montessori teachers begin with the story of the Coming of the Universe.

If you look at the bottom of the stack of nested bowls in the picture, you can see that Montessori teachers begin with the story of the Coming of the Universe.

We start with the whole and move to the parts.

Each story draws from different subjects. Chemistry, geology, astronomy, and physics are addressed in the 1st Great Lesson. Botany and zoology are addressed when we teach about the Coming of Life on Earth, and we move to anthropology, archaeology, and history as we tell the Coming of Humans Great Lesson, etc.

Why did Maria and Mario Montessori develop these stories? They thought that developmentally, young children are ready to consider significant issues. Starting at age six, children are leaving their families, thinking about how they fit into a larger social context. As they start to ask deeper “why” and “what” questions, why not give them the whole universe?

To interest the children in the universe, we must not begin by giving them elementary facts about it, to make them merely understand its mechanism, but start with far loftier notions of a philosophical nature, put in an acceptable manner, suited to the child’s psychology. (Montessori, 1989, p. 28)

Montessori teachers use these stories for several reasons:

- as a springboard to awaken wonder and curiosity. The stories are not told to memorize all the facts about the big bang theory, for example, but to touch imaginations so that children are inspired to ask more questions and seek information about those questions.

- to suggest a framework of interrelated information that leads to independent study.

- to address the interdependence across the whole system, rather than teaching using isolated parts: “Children’s minds are not divided into categories. They operate as whole systems.” (Lillard, 1996, p. 59).

- to build respect and reverence for all that has come before and during human time on Earth.

Montessori elementary teachers teach the stories (Great Lessons) at the beginning of each year. We don’t always finish them in the first month of school. Sometimes we stretch them out a little longer, depending on whether the students take off exploring lessons that they have heard. And we keep follow up lessons “flowing” while we follow the children and what they are inspired to study after hearing the story. Then we tell the next story.

What’s really interesting about these stories is that they draw the teacher AND the student into important learning. The stories give Montessori teachers a framework for organizing their work, and a way to be intentional about planting seeds of wonder in children. Every year, I went back and reviewed the basic outline of the stories developed by Maria and Mario Montessori, and then I reviewed story-telling techniques, about how to bring new energy into telling of the stories. I found that this made me excited about starting each new year. For the children, the stories are a seed-planting experience, getting the children engaged and awakening the questions that they might have and the research they can work on throughout the year.

There are charts and scientific experiment materials that go along with telling the stories. .All of these materials need to be prepared in advance. In the days before we start the stories, we whisper to the children that we will be telling very special stories. The older children hold this secret (having heard the stories in previous years). They whisper to the younger children that special stories are about to be told. Excitement builds. The day the children walk into class and see that the windows are covered and/or the blinds are down, they know that this is an indication that this is finally the day that the first Great Lesson will be told. Many types of journals are set up, too, so that the children are ready to start working on questions that inspire them after they hear the stories.

How Do These Stories Plant Seeds of Wonder?

The stories are told in lower elementary—(Montessori classrooms combine 1st, 2nd, and 3rd grades)—and they are also told in upper elementary (4th, 5th, and 6th grades) and in the older grades, too (sometimes 6th grade is in a public Montessori middle school). The teachers in the older grades add on to these stories in a very sophisticated way. So if you are a Montessori student, you hear these stories over and over again, with more details added on each year, and the questions the children ask are more sophisticated each year.

In this picture  the teacher is set up for the first Great Lesson. Usually we ask the children to sit on the floor, but in this class, they are sitting in chairs. You can see all the scientific experimental material on the table. This teacher is going to tell the Coming of the Universe story. It includes the scientific theories such as the big bang theory.

the teacher is set up for the first Great Lesson. Usually we ask the children to sit on the floor, but in this class, they are sitting in chairs. You can see all the scientific experimental material on the table. This teacher is going to tell the Coming of the Universe story. It includes the scientific theories such as the big bang theory.

The story includes expansionist theories, and any new scientific theories that have come along can be added into the story. We also tell stories that come from ancient traditions. But once again, it’s not every fact and detail; it is an impressionistic story. Charts are used, like these charts seen in this picture and then, once the story is told, children start asking questions like: “How does gravity work?” “Why don’t the planets fall out of the sky?” “How do volcanoes work?” As soon as the teacher starts hearing these types of questions, he or she guides the students to go off and begin research on these questions. There are additional stories and scientific lessons that continue to follow the main story–such as:

- scientific states of matter

- the birth and death of stars

- the creation of the solar system

- volcanoes

- creation stories.

The second story or Great Lesson is “The Coming of Life on Earth.” We use several materials to tell this story. This story tells about how creatures came to life on Earth… as we unroll the Timeline of Life we show the children the very simple, single celled creatures that were created on Earth. Then the story goes on as we unfold the Timeline of Life to talk about the jelly fish as an ancient creature, the trilobites (that became extinct), and as the timeline opens all sorts of sea, air, and land creatures are discussed on the timeline. A blank timeline is also included with this material so that the children can use it to memorize where each creature goes on the timeline, or to match the creatures from the original timeline. This Great Lesson inspires a lot of work in biology and zoology.

When the children see the timeline and the “Coming of Life” stories, they begin asking questions such as:

“What happened to the trilobites?” “Why aren’t the dinosaurs here anymore?”

They may begin studying fossils and how scientists tracked different creatures that lived on earth through the fossil record. We also give lessons on the plant and animal kingdoms. We teach songs so the children can memorize the 5 kingdoms of life etc. In lower elementary (1st-3rd) many children carry out animal research.

Then we move to animal husbandry. We go out to farms to see live animals and encourage the children to continue their research with live animals. Children love to do research on different plants in our own classroom gardens. Montessori teachers develop a lot of materials to add into the follow-on lessons after the Coming of Life story is told.

This is a child actually teaching other chi ldren about the research that she did. Thus, one of the outcomes of these stories is the cross-fertilization that begins to happen between children. The teacher tells the Great Lesson, but the children also present information to each other.

ldren about the research that she did. Thus, one of the outcomes of these stories is the cross-fertilization that begins to happen between children. The teacher tells the Great Lesson, but the children also present information to each other.

Thus this cyclical pattern begins to happen:

We use another timeline to tell the “Coming of Humans” story. It includes pictures that demonstrate the unique qualities of humans—like demonstrating the importance of using the pincer grip, human’s unique ability to use hands to create; about how humans discovered fire, and how humans take care of young and elders. Also, it depicts the human capacity to bury those who die. In this story we talk about the human capacity for empathy. (For example, we can feel for others who lived through a tsunami, even though we haven’t lived through it ourselves). This leads to the study of ancient civilizations.

We use another timeline to tell the “Coming of Humans” story. It includes pictures that demonstrate the unique qualities of humans—like demonstrating the importance of using the pincer grip, human’s unique ability to use hands to create; about how humans discovered fire, and how humans take care of young and elders. Also, it depicts the human capacity to bury those who die. In this story we talk about the human capacity for empathy. (For example, we can feel for others who lived through a tsunami, even though we haven’t lived through it ourselves). This leads to the study of ancient civilizations.

Here are some examples of follow-on lessons that come after the “Coming of Humans” story:

- fundamental needs of humans

- history of tools

- ancient civilizations

- history of transportation

- history of medicine.

This child is working on a timeline about ancient China.

We also go out of the classroom—for example, to museums and galleries—to learn about the history of humans in our communities.

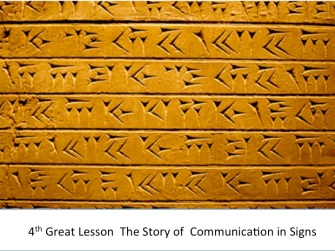

The fourth story or “Great Lesson” is the Story of Communication in Signs. This is when we talk about how humans learned to communicate through writing and reading. We talk about the ancient Egyptians and cuneiform writing (and many other ancient scripts). This is a fascinating story for young children who are learning to read because they begin to realize they are not alone in this endeavor… that all humans developed the skill of reading and writing over time. Some of the follow-on stories that are told after this Great Lesson are about

- diverse alphabets

- origins of writing utensils and paper

- development of the printing press

- history of fax and computer

- continuation of the study of ancient civilizations and their means of communication

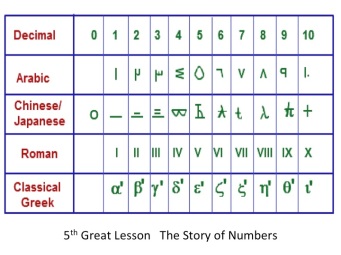

The 5th story (Great Lesson) is called the Story of Numbers. Ancient humans needed a way to communicate through trading. The “Story of Numbers” is about how ancient ways of counting began. It includes stories, for example, about how the Mayans piled stones up to count and how Arabic numerals evolved. Interesting stories continue to be told afterwards. Here are some examples of follow-up stories and lessons related to the “Story of Numbers:”

- How zero was “born”

- Continued history of counting

- History of math principles

- Development of calendars

- Systems and units of measurement

- Economic geography.

Basically the whole concept of teaching these stories is to help students realize that they have the power within themselves to ask powerful questions as they listen to the stories. It is our job as Montessorians to listen to their questions, to decide how we can guide their interests, and to support them as they do their research.

Does this mean there is total unstructured time in the classroom?

Of course, in public schools, Montessori teachers must follow the state curriculum each year. We start with the five great lessons, and student interest and research are inspired through hearing the stories. It is our job as Montessori teachers to keep an eye on the state curriculum but also to honor the children’s questions. We try to weave the content from the state curriculum with where the students are trying to go with their questions. So there is structure in that we have the aligned curriculum from the state, as well as the Montessori curriculum. In fact, people have spent a lot of time aligning these two curricular documents to give us a structure so that children have access to both of them. It is not just a jumble but has structure.

What about the testing mandates in public schools?

We are still curious about the future of Montessori in the public schools and what’s going to happen to us with all the testing requirements. There is a dis-connect between Montessori teaching and the amount of stopping and starting that happens to accommodate test-taking. Our concern is about the large numbers of tests and how tests interrupt the dynamic flow that happens when we get all these threads flowing. This picture, in fact, is an actual stack of my testing materials for a year in a public Montessori school.

Once these “Great Lessons” are told, it’s not a linear process where we are only studying “the plant cycle” or the “animal kingdom.” The children are involved in a complex inquiry process including follow-on lessons and independent research. And then the children are expected to sit down and take a test only in reading or only in math. It simply interrupts the flow.

Kids often want to go to these deeper places, and there isn’t time because you have to hit all the reading, writing, and math skills in the state standards. We strive to keep this dynamic flow of storytelling, experimenting, researching, and reporting continuing, but the children are interrupted constantly by required testing. In the evolution of the standards and the testing systems, there are some opportunities for performance-based assessments, however, which can be integrated into the flow of students’ questions.

Telling the Great Lessons and observing children in follow up provides data, too—as we watch students interact, as we watch them explore the lessons and complete their research. It makes sense to watch for patterns in their interactions across time. This information can tell us a great deal about what and how children are learning.

So what did we do at my school to work on keeping this opportunity for keeping complexity alive in our classrooms?

- We tried to protect a three-hour uninterrupted work period. Children could stay in the classroom and keep the cycle going.

- But that didn’t stop the amount of interruption to take the tests so we’d like to keep this conversation alive, to see what other adjustments might be made.

What more can we do?

- Stories provide data, too. Stories that we get as we watch the students interact – without making it a test – is really important. We can look for other ways to measure to replace or supplement traditional testing data.

- Keep avenues open for allowing complexity to thrive in each classroom rather than shutting down these avenues by designing structures and rules that promote the exact opposite.

- Let’s continue to question the way we are collecting evidence to prove that learning is taking place. What outcomes do our methods produce? It is not easy to do so but worth every effort for the sake of the children.

Now What?

Other approaches are similar to these “Great Lessons” if other teachers would like to use these stories as a framework to guide instruction. For example, David Christian developed an approach called “Big History,” which is similar to the Montessori “Great Lessons.”

Big History can be used in high schools and universities. The challenge is to take all the Common Core that is written and weave these standards into the art of storytelling using Big History. It’s a huge job when information is taught in silos of isolated subjects. However, “leaning in” to try to weave it all together is a worthy endeavor.

We must continue our “courageous conversations” about how to teach in an interdisciplinary way, to preserve space for this type of storytelling that inspires children to ask important questions about significant issues, and to preserve the time for children to explore findings. By doing so we honor the complexity that is inherent in helping each child develop his or her full potential.

References

Duffy, M. and D. (2013). Children of the Universe: Cosmic Education in the Montessori Elementary Classroom. Santa Rosa, CA: Parent Child Press.

Lillard, P. P. (1996). Montessori today: A comprehensive approach to education from birth to adulthood. New York: Schocken Books.

Montessori, M. (1989). To educate the human potential. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO Ltd; 1st Paperback Edition.

Montessori, M. (1994). From Childhood to adolescence: Including Erdkinder and the Function of the University. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO Ltd; 1st Paperback Edition.

Thanks for the images. . .

- The Coming of the Universe and Earth https://www.google.com/imgres?imgurl=http%3A%2F%2Fcdn.playbuzz.com%2Fcdn%2F5e9578bd-2fdc-4133-a33e-dc8116d98f3a%2F23ca6bdd-0c21-4872-a486-7902e9077e92.jpg&imgrefurl=http%3A%2F

- The Story of Life on Earth: http://montessorinuggets.blogspot.com

- The Coming of Humans: http://www.pinegreenwoods.com/thecomingofhum ans.htm

- The Story of Communication in Signs: http://www.flickr.com/photos/jvdc/

- Nested Great Lesson Sequence: https://www.pinterest.com/laurenkni ght9/montessori/

- Teacher and class: http://riverruncommunitymontessori.blogspot.com

- The children in Mary Beth Wertimes’ elementary Montessori classes at Drew Model School in Arlington, VA. (Thanks to ALL her students, but space considerations allowed us to include only a few of the pictures.)